In my last post, I shared some thoughts about “civic tech,” a new(ish) sector focused expressly on the public good. This definition opens countless roads for exploration, and yet many are not currently taken. Radical innovation hasn’t disrupted voting, political discourse or wealth structures. Say what you will about the cult of disruption, I am optimistic that the civic tech movement will improve our public sphere. That’s what I’ll focus on in this second edition of my Civic Tech Primer series.

Before we jump down the disruption rabbit hole, a brief tour of civic tech market saturation in 2015 may be instructive. Digital advocacy and online campaigning tools like Nationbuilder and Mobile Commons have proliferated, largely through the impressive spend of the nonprofit development and political campaigning realms. Crowdfunding now stands as an important add-on funding channel for nonprofits, community groups and social enterprises alike, with companies like Neighborly and Classy leading a field expected to raise $34.4 billion globally in 2015. And we’ve seen recent explosive growth and competition in the political engagement space, where sites like Countable, Brigade and dozens more hope to transform how citizens interact with their governments.

Outside of these clusters of activity, where is the civic tech opportunity? I put this question to my network and received a plethora of interesting perspectives which I’ll share, followed by my own.

Where is the civic tech opportunity?

The most popular response centered around public input channels and polling, particularly for the benefit and evaluation of decision making by elected officials. Given our current mobile-social addiction, real-time, proactive polling on citizen opinion policy initiatives seems inevitable. San Francisco Mayoral candidate Amy Farah Weiss suggested specifically that residents need a way to “proactively assess and request [the] needs of their neighborhood in order to shape (rather than just react) to development.” Ultimately, how can we provide our elected officials the data they need to make the best decisions possible, while evaluating the impact of those decisions?

Similarly, despite the abundance of data–big, open or otherwise–we still haven’t seen reporting, analysis and visualization tools that can help with decision-making, especially at the policy level. The recent $25 million investment in OpenGov by Andreessen Horowitz is an indicator that this may soon change.

Another area of interest was co-budgeting. Known as “participatory budgeting” in the public sector, this constitutes a process of democratic deliberation and decision-making in which citizens decide how to allocate part of a public budget. I’m also inspired by collaborative funding processes being seen in organizations like the Enspiral Network who allocate funding across their collective via their CoBudget tool. Talk about eating your own dog food.

I was somewhat surprised by a call for utilizing existing resources, be they public libraries or public-private partnerships. This brings up an important question…is it always best to build outside of institutions, as is often the impulse of “disruptive” entrepreneurs? Hillary Hartley, Co-founder of federal digital services agency 18F, reflected this in her plea for more sustainable business models: “Many things need to be disrupted, but it’s easier said than done if you don’t understand how government actually works or what you have to work with.”

The killer app for civic tech

No, I don’t believe there will be one killer app for civic tech. There will be many attempts, many failures, and a few critical success, but we must learn from them all. Here’s what I’m most excited about that I don’t see happening just yet:

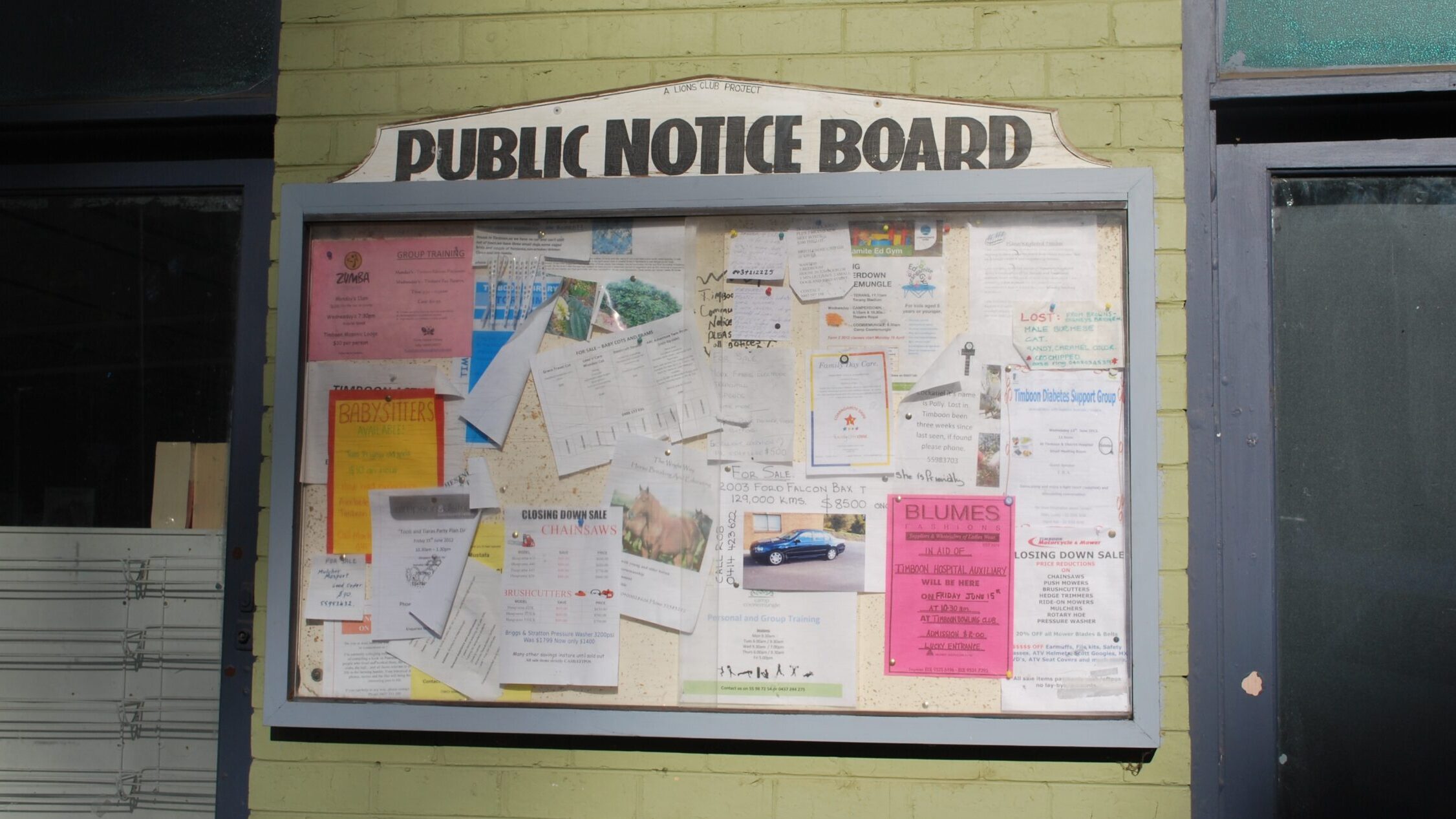

An enormous opportunity exists to transform the broken public input process for government at all levels. For some time now, I’ve had the idea for a “Public Input Directory” that would track all channels by which citizens can provide input to local agencies, from front desks to web forms, public hearings to social media profiles. Such a mapping exercise could be completed with volunteer help, then results published and a gap analysis performed to offer suggestions about how to improve the public input process and engage more citizens, more of the time. Start in one city willing to partner, then roll out to every other city around the world. I suspect that ample opportunities for innovation and business models would emerge from this exercise.

One specific public input channel yearning for change is the public meeting. These meetings may be the definition of broken, as Catherine Bracy of Code for America notes in her Personal Democracy Forum talk. Be it new formats or new tools for collecting input, the humble public meeting needs some attention.

I’m also excited by the possibility of translation and interpretation. The low hanging fruit here is language and cultural translation efforts. One of my recent favorites is 18 Million Rising’s VoterVox, a crowd-translated voting guide app for Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. But translation extends further, like the efforts of Healthy Democracy, whose Citizens’ Initiative Review, brings representative groups of citizens together to fairly and thoroughly evaluate ballot questions to give voters information they can trust.

For all the talk of transparency, I hear little conversation in the civic tech space of the potential for utter, total and radical transparency by using blockchain as a system of record. Blockchain is “distributed database that maintains a continuously growing list of data records that are hardened against tampering and revision.” This technology has gained attention primarily through cryptocurrencies, but any identity system for online transactions can benefit from this public ledger approach. Right now, we can only speculate as to the social, economic and political implications, but adopting blockchain may just change the rules of the Internet game entirely.

In the end, I feel the biggest opportunity is not technology, but the process by which we make decisions together. At the highest, most formalized levels of group organization, this includes new forms of voting, like delegative or “liquid” democracy wherein one assigns their vote to a trusted proxy. But process also applies to the most humble of group decisions, whether in a meeting with colleagues or a discussion with neighbors. More often than not, we do not explicitly establish the rules by which our groups operate together. If we are not clear about how decisions will be made, how can we ever feel good about the outcomes?

I believe that improving our decision-making intelligence is critical for our 21st century society. What is the framework we are using to make decisions together? Are the necessary stakeholders at the table, and are those voices being considered? What group process feels right for the discussion at hand? Improving how we agree and disagree is hard work, but this is true innovation.

And that’s the civic tech opportunity as I see it. What am I missing? And what are you building? I’d love to know. And please stay tuned for the next post and a discussion of civic tech business models.